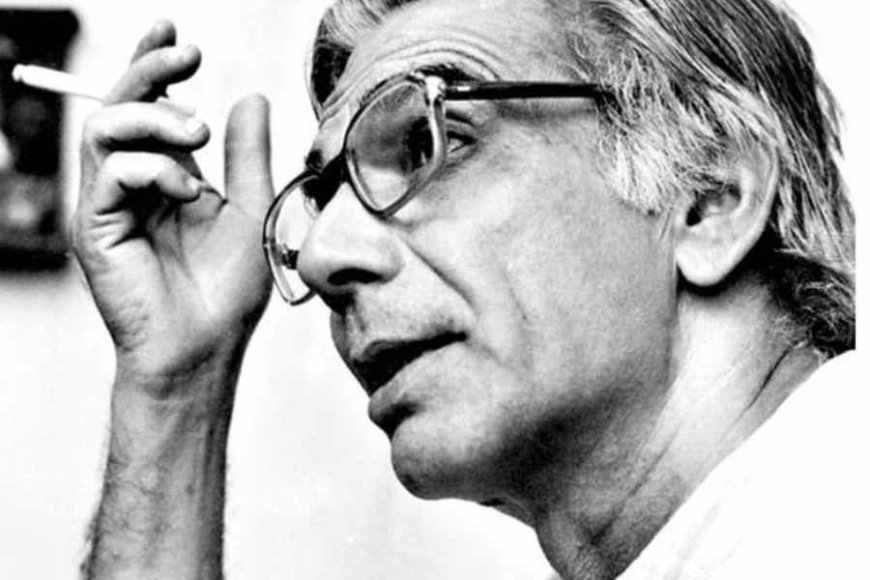

Remembering Bansi Chandragupta: The Artistic Architect of Indian Cinema

A Tribute to the Master Craftsman Behind Satyajit Ray's Iconic Sets

The ancient, beaten, craggy, colorless wooden doors in Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali, which an enraged Indir Thakrun pulls open to depart because she feels she has been accused of encouraging little Durga to steal fruits from neighbors, are crumbling and ancient, but they stand strong, much like Indir Thakrun. They turn into a picture of her.

Bansi Chandragupta, widely regarded as the finest art director in Indian movie history, created these doors. He designed settings for Ray's films, ranging from Shatranj Ke Khiladi to Pather Panchali, that are regarded as distinct universes because to their exquisite details. Sarbajaya sweeps and cleans the courtyard of the Kashi (Varanasi) home in Aparajito as part of a set. The interiors of Charulata, which crystallize in their precise, exquisite detail (the creation of the wallpaper by Chandragupta is another tale), are just as remarkable as Wajid Ali Shah's court in Shatranj Ke Khiladi, even as Charu floats around her own house, lovely, alone, and a stranger.

Bansi Chandragupta created Pather Panchali's wooden doors.

It is the centenary year of Chandragupta. The documentary Bansi, With & Without Ray, about him, was shown at Uttarpara Cine Club on Sunday in an effort to commemorate his extraordinary life, which is all but forgotten. The film, directed by Arindam Saha Sardar, recounts the tale of Chandragupta's life and accomplishments in a sensitive and nuanced manner without going beyond in terms of biography.

It also serves as a reminder that Chandragupta was not Ray's only employee.

After moving to Calcutta from Srinagar to follow artist Subho Thakur and pursue his own artistic career, Chandragupta met Ray in the 1940s. He was born in what is now Pakistan, in Sialkot.

He collaborated with Ray as an art director on Panther Panchali (1955), a film that transformed Indian cinema by moving it away from the dramatic and theatrical and toward contemporary realism. One of the masterminds behind this transformation is Chandragupta, who together with Ray and cameraman Subrata Mitra created a renowned triumvirate.

Still from Jalsaghar, directed by Satyajit Ray.

Filmmaker Moloy Bhattacharya discusses the Pather Panchali doors in the documentary. The doors were added to a genuine home in Boral village, outside of Calcutta, where Pather Panchali was filmed. Chandragupta broke down, stripped two new doors of their color, and worked on them very carefully.

Moloy Bhattacharya continues, "They became a reflection of Indir Thakrun."

Weathering was the term for the procedure, which is no longer used. Weathering gives an inanimate item a lived-in quality by adding time's marks on the film.

In this art, Chandragupta was a master. He tenderly, methodically, and meticulously constructed universes and gave everything life. A gregarious, modest, happy, and well-liked person, he spoke his opinions and didn't give up until he was content.

Still from Shatranj Ke Khiladi, directed by Satyajit Ray.

Even Ray, who was renowned for his strict timekeeping, would hold off on playing until Chandragupta had completed a set.

This pursuit of perfection could inspire creative ingenuity. Mitra wanted the scene of Sarbajaya and Harihar's Varanasi in Aparajito, which was supposed to be in a little lane, to have low light and to be shaded from above. That's what Chandragupta accomplished; light reflected from the top seemed to be streaming in from below. At the screening, Somesh Bhattacharya from Uttarpara Cine Club said, "This was the beginning of bounce lighting," but no one thought to mention it in the press.

The whole train in Ray's Nayak is a Chandragupta set. The dancing hall was a set at Aurora Studio in Calcutta, but the zamindar's residence in Jalsaghar was the Nimtita palace.

Though he continued to sketch, Chandragupta was unable to pursue his education in art at Visva-Bharati. However, this was art's loss and cinema's gain. Chandragupta first encountered set design while working with acclaimed production designer Eugène Lourié on the sets of Jean Renoir's 1951 Calcutta film The River.

Ray was a collaborator with Chandragupta from Pather Panchali to the 1960s.

Chandragupta has collaborated with a number of notable filmmakers both within and outside of Bengal, including Mrinal Sen, Tarun Majumdar, Aparna Sen, Shyam Benegal, James Ivory, and Kumar Sahani. Mrinal Sen recounted in the documentary how Chandragupta had modeled the inside of a falling house in the rain for his film Calcutta 71. Majumdar recounted how Chandragupta would use his own wages to cover set expenses for his movie Palatak. He was seeking artistic fulfillment rather than financial gain. In the documentary, Majumdar adds, "He told me if you don't make Balika Badhu, I will never work with you again."

According to Saha Sardar, the documentary's creator, they spoke with individuals who had strong ties to Chandragupta. The 2012 documentary has interviews with film editor Dulal Dutta, cinematographers Soumendu Roy and Purnendu Basu, and art directors Suresh Chandra Chandra and Kartik Basu. The directors of the documentary are Mrinal Sen, Majumdar, Aparna Sen, and Moloy Bhattacharya. "We decided to speak with the primary sources—those who had intimate knowledge of Chandragupta's work," adds Saha Sardar.

Chandragupta moved to Bombay, or Mumbai, in the early 1970s to work in the Hindi film business. Even though he was brilliant, he found work difficult. His pursuit of excellence often caused deadlines and finances to be pushed, and not all producers were eager to work with him. In another instance of his refusal to follow the rules, he lost his employment in a movie because he would not give up smoking in front of Kanan Devi.

He was cast in popular movies, such as Jungle Mein Mangal (1972), for which he created a set so magnificent that it attracted tourists. However, this was not his intended outcome.

Ray needed to get Chandragupt back when he made the decision to shoot Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977). The movie demonstrated Chandragupta's skillful recreation of grandeur. There would be a productive time after this. 1981 saw the release of three noteworthy movies, Kalyug (Shyam Benegal), Umrao Jaan (Muzaffar Ali), and 36, Chowringhee Lane (Aparna Sen), all of which included Chandragupta creating the sets.

Not every movie will be released in Chandragupta. He passed away from a heart attack in June 1981 while traveling to the US with Ray and film critic Chidananda Dasgupta. He was fifty-seven.

Along with Subho Thakur, Chandragupta had founded the Calcutta Film Society during his formative years in Calcutta and was a member of the radical artists' collective Calcutta Group. Along with many other Left-leaning individuals, he would be a part of the adda at Paradise Cafe that was attended by Mrinal Sen, lighting designer Tapas Sen, musician Salil Chowdhury, and director Ritwik Ghatak. Chandragupta and Tapas Sen had shared a room as "unemployed youths."

Black and white footage is used in the documentary about him. According to Saha Sardar, "If color is drained from a world full of color, a new dimension emerges." Certain things must be revealed in a brutal way.

Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by Press Time staff and has been published from a syndicated feed.