Farmers in India Renew Protests, Demanding Legislative Assurances Amidst Economic Grievances

Demonstrations reignite in Punjab, signaling discontent with Modi government's handling of rural issues

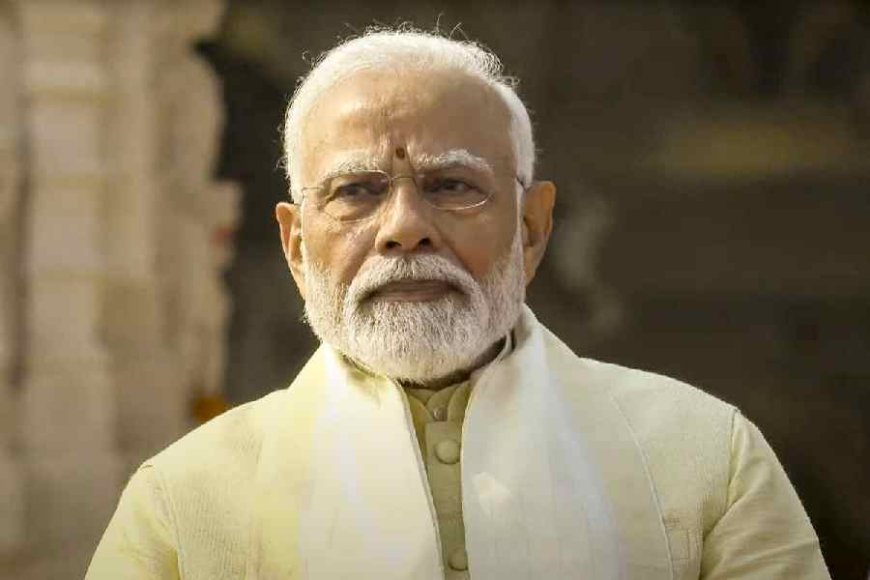

Farmers had been protesting for more than a year, and it seemed that he had won them over when India's strong Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided in 2021 to revoke three agricultural laws intended to modernize the outdated agriculture system.

However, less than two years later, farmers are once again waging battle in the politically delicate north of the most populous country in the world, demanding legislative assurances for a minimum purchase price for every crop. The demonstration takes place just a few months before the May general election.

While the farmers' protests are currently limited to Punjab, the breadbasket state of India, their grievances about declining incomes are felt throughout the vast rural hinterland of India, where there is a belief that Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have not done enough to improve living conditions for farmers.

More over 40% of India's 1.4 billion people are employed in agriculture, and many claim that under Modi, their economic situation has deteriorated relative to that of their urban counterparts.

The resentment of farmers will be a pain for years to come, despite pollsters predicting that Modi's reputation as a tough, no-nonsense leader and his forceful brand of majoritarian Hindu nationalism would almost likely win him a rare third term in government.

According to Uday Chandra, an associate professor of government at Georgetown University in Qatar, "the anger is spilling over because, unlike most Asian countries, India has failed to move people out of agriculture."

"The current protest will not harm the BJP in elections, but Modi has a really serious issue to deal with in his next term in office."

Hundreds of Punjabi farmers launched their protest earlier this month with the goal of reaching Delhi, the nation's capital. About 200 kilometers (125 miles) from the city, near the border with the neighboring state of Haryana, they were stopped by police and paramilitary personnel at Shambhu.

To stop the farmers' convoy of tractors and trucks, authorities blocked the route with rows of metal spikes and barbed wire and concrete obstacles.

For many days, footage of farmers and security personnel fighting with repeated cane charges and drone-dropped tear gas grenades has been playing on television. According to the farmers, several protestors on both sides have been hurt, and at least one protestor has died in the altercations.

Punjabi farmer Satpal Singh, standing by his tractor near the Shambhu border, wore a green turban and said, "Modi has not fulfilled his promises. I will not return to my fields until our demands are met."

Modi, according to Singh and other farmers, broke a pledge made in 2016 to increase their earnings by 2022. Rather, they have been denied access to international markets and higher prices due to a series of export restrictions on wheat, sugar, onions, and the majority of rice grades. These restrictions were put in place to limit consumer prices.

SET FOR THE LONG JOURNEY

India's embattled opposition parties have united behind the protesting farmers in an attempt to undermine Modi's meticulously constructed strong-man image.

Preparing for the prospect of having to face tear gas shells from security forces, Singh, who is also a member of the opposition Congress party's farmers' wing, collected 600,000 rupees ($7,240) from his fellow growers before to the march to purchase medication and gas masks.

With the help of tarpaulin sheets and tents, the farmers have transformed their tractors and trailers into temporary dwellings. They have also established communal kitchens that are stocked with wheat flour and vegetables from neighboring communities.

Punjabi Congress leader Sukhpal Khaira, a farmer, said, "We have not been able to defeat Modi, but we have created some disruption for the right reason."

Farmers and opposition leaders believe that the protest will deflate Modi's popularity and expand outside Punjab, similar to the 2020–2021 movement.

In an attempt to appease the farmers, the administration has convened many rounds of negotiations, but to no effect.

According to BJP national spokesman Shehzad Poonawalla, voters are aware of Modi's government's dedication to assisting the underprivileged and its efforts to resolve farmers' issues.

A CRISADE IN THE NATION

Farmers from other regions of the nation have also pointed to declining incomes—which are made worse by export restrictions—and less expensive imports as indicators of a worsening crisis in the rural areas, despite the fact that the protest is mostly limited to Punjab.

"The government outlawed onion exports just before harvest, which caused prices to plummet from 40 rupees per kg to only 8 rupees. How can our manufacturing expenditures be recouped?" In the western region of the nation, in Nashik, farmer Jagannath Ghorpade, who had planted the crop on a two-acre tract, was questioned.

Other farmers in western India have reported that a significant drop in the import duty on edible oils—from 30% in 2021 to 5.5% in 2022—has resulted in record imports of vegetable oil and lowered local prices for oilseeds like soybean and rapeseed.

Devinder Sharma, an independent specialist on farm and food policy, said that while the government now only gives minimum purchase prices for wheat and rice, there have only been very small rises in these prices.

According to official statistics, the government-fixed minimum purchase prices for wheat and rice increased by 63% and 67% during the 10 years of Modi's leadership, respectively, compared to 138% and 122% over the preceding ten years.

Over the last nine years, the agriculture sector in India, which makes up around 15% of the country's $3.7 trillion GDP, has risen at an average annual rate of 3.5%, while the industrial and services sectors have developed at an annual rate of over 6%.

The central bank claims that throughout the last nine years, farm financing has increased thrice to around 20 trillion rupees. Based on official figures, nearly 50% of India's 93 million agricultural families are heavily indebted, with each family owing an average of 74,121 rupees in loans.

According to ICRA, the Indian division of rating agency Moody's, the rate of increase in real rural wages was around 1% in 2023 after a contraction of over 3% in the preceding two years, but typical earnings in urban regions have been increasing at a pace of nearly 10% annually.

Arun Kumar, a former economics professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, said, "The imbalance between urban and rural India has widened in recent years, and that imbalance will only get wider if the government does not address the crisis in agriculture."

"India's policymakers will have to work on a series of measures to ensure that farming becomes viable and rural incomes go up."