The Man Behind the Icon: Understanding Ritwik Ghatak's Films

A Look Beyond the Posters and Mugs

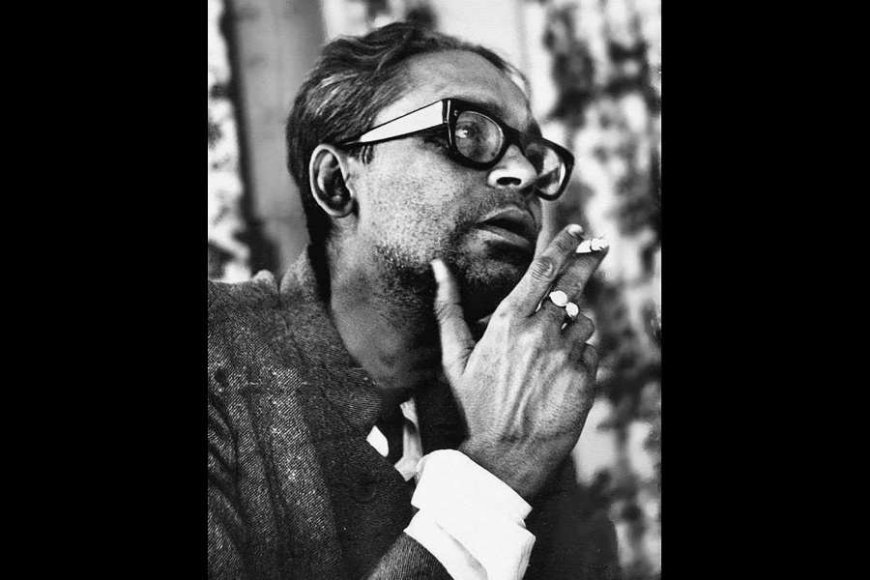

Ritwik Ghatak, who passed away almost 50 years ago, is now regarded as a "icon." More people than ever are pronouncing his name. About him, Martin Scorsese talks. He is the name of a Metro station in Calcutta. His scrawny visage was always photogenic; perhaps you'll see it staring back at you from t-shirts or mugs now that icons have found their final resting place.

An event that could spark a surge in this kind of action is approaching: the incredible director will shortly be 100. His birthday is November 4, 1925. The centennial festivities have commenced.

Consequently, some people are terrified. For the icon, iconization hasn't always been beneficial. Tagore is evidence that veneration hasn't aided comprehension of his writings. Conversely, though.

Ritwik's films are rarely understood, therefore a "Ritwik pujo" will be doubly terrible. He would have preferred his films to acquire an audience over just becoming iconic. A big one.

Nonetheless, part of the issue was his persona, which was always quite apparent. "His eclectic creativity and alcoholism were his hallmarks when he passed away on February 6, 1976," according to Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay, a former film studies professor at Jadavpur University in Calcutta.

He chuckles, "Ritwik was a counter-cultural figure and an anti-establishment figure for the Bengali middle class, which clubs together Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Manik Bandyopadhyay, and Ghatak."

The three men who passed away at the age of fifty matched Frank Kermode's description of the artist's archetype, which was self-destructive, "lonely, haunted, victimized, devoted to suffering rather than action."

At the Ritwik Akhra, an archive on the filmmaker, which opened on April 6 at the Jibansmriti Archive in Uttarpara, about 30 kilometers from Calcutta, Mukhopadhyay was one of the speakers.

Movie posters featuring works by Ritwik Ghatak

The archive aims to compile Ritwik's films—eight full-length and a number of short ones—as well as his essays, biographies, posters, movie-related materials, and other connected items.

According to Arindam Saha Sardar, the founder of Jibansmriti Archive, the response has been tremendous. He recently received a French poster for Ritwik's most well-known picture, Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960). In France, Ritwik has gained a great deal of praise.

The archive has a portrait and simple posters by artist Hiran Mitra that are inspired by Ritwik's flicks.

Mukhopadhyay claims that Ritwik was called a Partition filmmaker. Although he did discuss the Partition and the lives of refugees in Bengal, the Partition is not seen in his "Partition films," Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962). According to Mukhopadhyay, they portray estrangement and post-Partition pain.

Ritwik was less concerned in a specific incident and more in the plight of humanity.

This estrangement occurs everywhere on the planet. Unknown reasons are causing people to cross borders. This is happening in Palestine, close to the border with Mexico, according to Mukhopadhyay. or at the frontiers of Bangladesh, India, or Europe.

Not only does crossing the border include going between two geographically distinct locations, but it also involves a question of psychic dislocation. Ritwik uses a lot of homeless and displaced characters.

The protagonist of Ajantrik (1958), who calls his broken cab Jagaddal and cherishes it like a beloved human partner, lives in a desolate location. Ritwik's debut film, Nagarik (1952), was released following his death and had a strong theme of homelessness. In Komal Gandhar, Anasuya is caught between two places. Ritwik's recurring theme is dislocation.

The most astounding aspect of Ritwik's films, however, is how his radical reworking of our stories to build an allegorical framework supports the plot.

Another remarkable feature of his work was that, although being greatly affected by international cinema (Irwin was his biggest inspiration; he disapproved of Hollywood and its sophisticated narrative), every part of his films remained Indian.

Meghe Dhaka Kalidasa's Kumarsambhabam, which tells the tale of the union of Rudra, Shiva, the god of destruction, and Uma, the great mother, served as the inspiration for Tara, the story of a refugee family. The result of their union will be the birth of Kumar, the one who vanquishes evil.

However, given the current state of affairs, this union is not feasible. Rudra and Uma, or Shankar and Nita in this case, are siblings. However, the movie retells the story, with Nita joining Shankar as they sing "Je raatemor duarguli" and the scene suddenly focusing. By adding the sound of a whip to a Tagore song, the song itself made history.

According to Mukhopadhyay, "the song accomplishes the journey between the timeless and the temporal."

The camera focuses on a portion of Nita's neck in the shadows. It is lengthy and curved, resembling the goddess idol's neck. The brother and sister were shown, then lost, on screen. When they are hidden from view, they appear to enter a legendary era. Then the screen is filled with an impossible-low angle view of Nita's face. Her gaze is fixed elsewhere. She sees a peculiar glow on her face.

This is the last instant before the goddess drowns, right before Bisarjan. The sacrifice is the goddess, or the daughter of a family of refugees who has taken care of everyone. This is the historical trauma of India. The core of all of Ritwik's works is the cry of Nita, "Dada, ami banchbo (Dada, I want to live)."

According to Mukhopadhyay, the Shakuntala narrative serves as a leitmotif in Komal Gandhar and implicitly draws a connection to Shakespeare's Tempest.

Ritwik stated that although nature aids in the plot's progression in Western art, Shakuntala cannot be removed from the tapoban or removed from nature.

In Subarnarekha, Kaushalya, also known as "Bagdi bou," a woman from a lower caste, passes away at a train station without receiving proper care, while her son Abhiram, who was raised apart from her, is coincidentally present at that same location.

Sita is Abhiram's spouse. An epic has been adapted for modern-day India.

Ritwik's landscape is traversed by mythical beings disguised as people. "The core of Ritwik's films is a philosophical argument. Among Indian filmmakers, he is the most intelligent, claims Mukhopadhyay.

However, when the movies were first released, they were a little too much for a crowd that had grown up with a certain level of realism and entertainment value from movies.

Hollywood storytelling and realism were not Ritwik's cup of tea. According to Mukhopadhyay, "He introduced a discursive cultural practice that transcended plot or narrative."

Even the medium of film held no significance for Ritwik. "Cinema for me is nothing but an expression," he states in Cinema and I, an anthology of his amazing essays and interviews. I use it as a way to vent my rage over the tragedies and sufferings of my people.

If he had discovered a more powerful and immediate means of communication, he would have gone with it.

Ritwik will be remembered through an archive. Participating in the cinema club movement for a long time and having attended the inauguration, artist Mitra believes Ritwik is a weapon against modern culture, which she defines as the antithesis of culture or a lack thereof. He claims, "In our youth, he had burned us."

Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by Press Time staff and has been published from a syndicated feed.